http://robertreich.org/

It’s now possible to sell a new product to

hundreds of millions of people without needing many, if any, workers to

produce or distribute it.

At its prime in 1988, Kodak, the iconic American photography company, had 145,000 employees. In 2012, Kodak filed for bankruptcy.

The same year Kodak went under, Instagram, the world’s newest photo company, had 13 employees serving 30 million customers.

The ratio of producers to customers continues to plummet. When Facebook purchased “WhatsApp” (the messaging app) for $19 billion last year, WhatsApp had 55 employees serving 450 million customers.

A friend, operating from his home in Tucson, recently invented a machine that can find particles of certain elements in the air.

He’s already sold hundreds of these machines over the Internet to customers all over the world. He’s manufacturing them in his garage with a 3D printer.

So far, his entire business depends on just one person — himself.

New technologies aren’t just labor-replacing. They’re also knowledge-replacing.

The combination of advanced sensors, voice recognition, artificial intelligence, big data, text-mining, and pattern-recognition algorithms, is generating smart robots capable of quickly learning human actions, and even learning from one another.

If you think being a “professional” makes your job safe, think again.

The two sectors of the economy harboring the most professionals — health care and education – are under increasing pressure to cut costs. And expert machines are poised to take over.

We’re on the verge of a wave of mobile health apps for measuring everything from your cholesterol to your blood pressure, along with diagnostic software that tells you what it means and what to do about it.

In coming years, software apps will be doing many of the things physicians, nurses, and technicians now do (think ultrasound, CT scans, and electrocardiograms).

Meanwhile, the jobs of many teachers and university professors will disappear, replaced by online courses and interactive online textbooks.

Where will this end?

Imagine a small box – let’s call it an “iEverything” – capable of producing everything you could possibly desire, a modern day Aladdin’s lamp.

You simply tell it what you want, and – presto – the object of your desire arrives at your feet.

The iEverything also does whatever you want. It gives you a massage, fetches you your slippers, does your laundry and folds and irons it.

The iEverything will be the best machine ever invented.

The only problem is no one will be able to buy it. That’s because no one will have any means of earning money, since the iEverything will do it all.

This is obviously fanciful, but when more and more can be done by fewer and fewer people, the profits go to an ever-smaller circle of executives and owner-investors.

One of the young founders of WhatsApp, CEO Jan Koum, had a 45 percent equity stake in the company when Facebook purchased it, which yielded him $6.8 billion.

Cofounder Brian Acton got $3 billion for his 20 percent stake.

Each of the early employees reportedly had a 1 percent stake, which presumably netted them $160 million each.

Meanwhile, the rest of us will be left providing the only things technology can’t provide – person-to-person attention, human touch, and care. But these sorts of person-to-person jobs pay very little.

That means most of us will have less and less money to buy the dazzling array of products and services spawned by blockbuster technologies – because those same technologies will be supplanting our jobs and driving down our pay.

We need a new economic model.

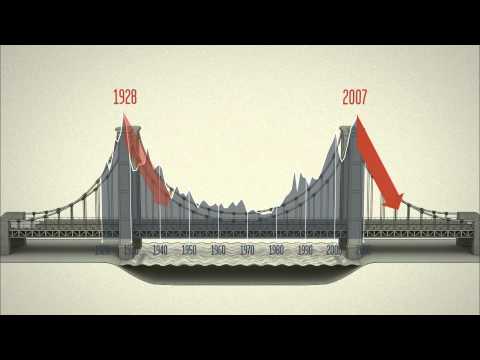

The economic model that dominated most of the twentieth century was mass production by the many, for mass consumption by the many.

Workers were consumers; consumers were workers. As paychecks rose, people had more money to buy all the things they and others produced — like Kodak cameras. That resulted in more jobs and even higher pay.

That virtuous cycle is now falling apart. A future of almost unlimited production by a handful, for consumption by whoever can afford it, is a recipe for economic and social collapse.

Our underlying problem won’t be the number of jobs. It will be – it already is — the allocation of income and wealth.

What to do?

“Redistribution” has become a bad word.

But the economy toward which we’re hurtling — in which more and more is generated by fewer and fewer people who reap almost all the rewards, leaving the rest of us without enough purchasing power – can’t function.

It may be that a redistribution of income and wealth from the rich owners of breakthrough technologies to the rest of us becomes the only means of making the future economy work.

At its prime in 1988, Kodak, the iconic American photography company, had 145,000 employees. In 2012, Kodak filed for bankruptcy.

The same year Kodak went under, Instagram, the world’s newest photo company, had 13 employees serving 30 million customers.

The ratio of producers to customers continues to plummet. When Facebook purchased “WhatsApp” (the messaging app) for $19 billion last year, WhatsApp had 55 employees serving 450 million customers.

A friend, operating from his home in Tucson, recently invented a machine that can find particles of certain elements in the air.

He’s already sold hundreds of these machines over the Internet to customers all over the world. He’s manufacturing them in his garage with a 3D printer.

So far, his entire business depends on just one person — himself.

New technologies aren’t just labor-replacing. They’re also knowledge-replacing.

The combination of advanced sensors, voice recognition, artificial intelligence, big data, text-mining, and pattern-recognition algorithms, is generating smart robots capable of quickly learning human actions, and even learning from one another.

If you think being a “professional” makes your job safe, think again.

The two sectors of the economy harboring the most professionals — health care and education – are under increasing pressure to cut costs. And expert machines are poised to take over.

We’re on the verge of a wave of mobile health apps for measuring everything from your cholesterol to your blood pressure, along with diagnostic software that tells you what it means and what to do about it.

In coming years, software apps will be doing many of the things physicians, nurses, and technicians now do (think ultrasound, CT scans, and electrocardiograms).

Meanwhile, the jobs of many teachers and university professors will disappear, replaced by online courses and interactive online textbooks.

Where will this end?

Imagine a small box – let’s call it an “iEverything” – capable of producing everything you could possibly desire, a modern day Aladdin’s lamp.

You simply tell it what you want, and – presto – the object of your desire arrives at your feet.

The iEverything also does whatever you want. It gives you a massage, fetches you your slippers, does your laundry and folds and irons it.

The iEverything will be the best machine ever invented.

The only problem is no one will be able to buy it. That’s because no one will have any means of earning money, since the iEverything will do it all.

This is obviously fanciful, but when more and more can be done by fewer and fewer people, the profits go to an ever-smaller circle of executives and owner-investors.

One of the young founders of WhatsApp, CEO Jan Koum, had a 45 percent equity stake in the company when Facebook purchased it, which yielded him $6.8 billion.

Cofounder Brian Acton got $3 billion for his 20 percent stake.

Each of the early employees reportedly had a 1 percent stake, which presumably netted them $160 million each.

Meanwhile, the rest of us will be left providing the only things technology can’t provide – person-to-person attention, human touch, and care. But these sorts of person-to-person jobs pay very little.

That means most of us will have less and less money to buy the dazzling array of products and services spawned by blockbuster technologies – because those same technologies will be supplanting our jobs and driving down our pay.

We need a new economic model.

The economic model that dominated most of the twentieth century was mass production by the many, for mass consumption by the many.

Workers were consumers; consumers were workers. As paychecks rose, people had more money to buy all the things they and others produced — like Kodak cameras. That resulted in more jobs and even higher pay.

That virtuous cycle is now falling apart. A future of almost unlimited production by a handful, for consumption by whoever can afford it, is a recipe for economic and social collapse.

Our underlying problem won’t be the number of jobs. It will be – it already is — the allocation of income and wealth.

What to do?

“Redistribution” has become a bad word.

But the economy toward which we’re hurtling — in which more and more is generated by fewer and fewer people who reap almost all the rewards, leaving the rest of us without enough purchasing power – can’t function.

It may be that a redistribution of income and wealth from the rich owners of breakthrough technologies to the rest of us becomes the only means of making the future economy work.

The 3 Biggest Myths Blinding Us to the Economic Truth

1. The “job creators” are CEOs, corporations, and the rich, whose taxes must be low in order to induce them to create more jobs. Rubbish. The real job creators are the vast middle class and the poor, whose spending induces businesses to create jobs. Which is why raising the minimum wage, extending overtime protection, enlarging the Earned Income Tax Credit, and reducing middle-class taxes are all necessary.

2. The critical choice is between the “free market” or “government.” Baloney. The free market doesn’t exist in nature. It’s created and enforced by government. And all the ongoing decisions about how it’s organized – what gets patent protection and for how long (the human genome?), who can declare bankruptcy (corporations? homeowners? student debtors?), what contracts are fraudulent (insider trading?) or coercive (predatory loans? mandatory arbitration?), and how much market power is excessive (Comcast and Time Warner?) – depend on government.

3. We should worry most about the size of government. Wrong. We should worry about who government is for. When big money from giant corporations and Wall Street inundate our politics, all decisions relating to #1 and #2 above become rigged against average working Americans.

Please take a look at our video, and share.

1. The “job creators” are CEOs, corporations, and the rich, whose taxes must be low in order to induce them to create more jobs. Rubbish. The real job creators are the vast middle class and the poor, whose spending induces businesses to create jobs. Which is why raising the minimum wage, extending overtime protection, enlarging the Earned Income Tax Credit, and reducing middle-class taxes are all necessary.

2. The critical choice is between the “free market” or “government.” Baloney. The free market doesn’t exist in nature. It’s created and enforced by government. And all the ongoing decisions about how it’s organized – what gets patent protection and for how long (the human genome?), who can declare bankruptcy (corporations? homeowners? student debtors?), what contracts are fraudulent (insider trading?) or coercive (predatory loans? mandatory arbitration?), and how much market power is excessive (Comcast and Time Warner?) – depend on government.

3. We should worry most about the size of government. Wrong. We should worry about who government is for. When big money from giant corporations and Wall Street inundate our politics, all decisions relating to #1 and #2 above become rigged against average working Americans.

Please take a look at our video, and share.

The Conundrum of Corporation and Nation

Sunday, March 8, 2015

The U.S. economy is picking up steam but

most Americans aren’t feeling it. By contrast, most European economies are still

in bad shape, but most Europeans are doing relatively well.

What’s behind this? Two big facts.

First, American corporations exert far more political influence in the United States than their counterparts exert in their own countries.

In fact, most Americans have no influence at all. That’s the conclusion of Professors Martin Gilens of Princeton and Benjamin Page of Northwestern University, who analyzed 1,799 policy issues — and found that “the preferences of the average American appear to have only a miniscule, near-zero, statistically non-significant impact upon public policy.”

Instead, American lawmakers respond to the demands of wealthy individuals (typically corporate executives and Wall Street moguls) and of big corporations – those with the most lobbying prowess and deepest pockets to bankroll campaigns.

The second fact is most big American corporations have no particular allegiance to America. They don’t want Americans to have better wages. Their only allegiance and responsibility to their shareholders — which often requires lower wages to fuel larger profits and higher share prices.

When GM went public again in 2010, it boasted of making 43 percent of its cars in place where labor is less than $15 an hour, while in North America it could now pay “lower-tiered” wages and benefits for new employees.

American corporations shift their profits around the world wherever they pay the lowest taxes. Some are even morphing into foreign corporations.

As an Apple executive told The New York Times, “We don’t have an obligation to solve America’s problems.”

I’m not blaming American corporations. They’re in business to make profits and maximize their share prices, not to serve America.

But because of these two basic facts – their dominance on American politics, and their interest in share prices instead of the wellbeing of Americans – it’s folly to count on them to create good American jobs or improve American competitiveness, or represent the interests of the United States in global commerce.

By contrast, big corporations headquartered in other rich nations are more responsible for the wellbeing of the people who live in those nations.

That’s because labor unions there are typically stronger than they are here — able to exert pressure both at the company level and nationally.

VW’s labor unions, for example, have a voice in governing the company, as they do in other big German corporations. Not long ago, VW even welcomed the UAW to its auto plant in Chattanooga, Tennessee. (Tennessee’s own politicians nixed it.)

Governments in other rich nations often devise laws through tri-partite bargains involving big corporations and organized labor. This process further binds their corporations to their nations.

Meanwhile, American corporations distribute a smaller share of their earnings to their workers than do European or Canadian-based corporations.

And top U.S. corporate executives make far more money than their counterparts in other wealthy countries.

The typical American worker puts in more hours than Canadians and Europeans, and gets little or no paid vacation or paid family leave. In Europe, the norm is five weeks paid vacation per year and more than three months paid family leave.

And because of the overwhelming clout of American firms on U.S. politics, Americans don’t get nearly as good a deal from their governments as do Canadians and Europeans.

Governments there impose higher taxes on the wealthy and redistribute more of it to middle and lower income households. Most of their citizens receive essentially free health care and more generous unemployment benefits than do Americans.

So it shouldn’t be surprising that even though U.S. economy is doing better, most Americans are not.

The U.S. middle class is no longer the world’s richest. After considering taxes and transfer payments, middle-class incomes in Canada and much of Western Europe are higher than in U.S. The poor in Western Europe earn more than do poor Americans.

Finally, when at global negotiating tables – such as the secretive process devising the “Trans Pacific Partnership” trade deal — American corporations don’t represent the interests of Americans. They represent the interests of their executives and shareholders, who are not only wealthier than most Americans but also reside all over the world.

Which is why the pending Partnership protects the intellectual property of American corporations — but not American workers’ health, safety, or wages, and not the environment.

The Obama administration is casting the Partnership as way to contain Chinese influence in the Pacific region. The agents of America’s interests in the area are assumed to be American corporations.

But that assumption is incorrect. American corporations aren’t set up to represent America’s interests in the Pacific region or anywhere else.

What’s the answer to this basic conundrum? Either we lessen the dominance of big American corporations over American politics. Or we increase their allegiance and responsibility to America.

It has to be one or the other. Americans can’t thrive within a political system run largely by big American corporations — organized to boost their share prices but not boost America.

What’s behind this? Two big facts.

First, American corporations exert far more political influence in the United States than their counterparts exert in their own countries.

In fact, most Americans have no influence at all. That’s the conclusion of Professors Martin Gilens of Princeton and Benjamin Page of Northwestern University, who analyzed 1,799 policy issues — and found that “the preferences of the average American appear to have only a miniscule, near-zero, statistically non-significant impact upon public policy.”

Instead, American lawmakers respond to the demands of wealthy individuals (typically corporate executives and Wall Street moguls) and of big corporations – those with the most lobbying prowess and deepest pockets to bankroll campaigns.

The second fact is most big American corporations have no particular allegiance to America. They don’t want Americans to have better wages. Their only allegiance and responsibility to their shareholders — which often requires lower wages to fuel larger profits and higher share prices.

When GM went public again in 2010, it boasted of making 43 percent of its cars in place where labor is less than $15 an hour, while in North America it could now pay “lower-tiered” wages and benefits for new employees.

American corporations shift their profits around the world wherever they pay the lowest taxes. Some are even morphing into foreign corporations.

As an Apple executive told The New York Times, “We don’t have an obligation to solve America’s problems.”

I’m not blaming American corporations. They’re in business to make profits and maximize their share prices, not to serve America.

But because of these two basic facts – their dominance on American politics, and their interest in share prices instead of the wellbeing of Americans – it’s folly to count on them to create good American jobs or improve American competitiveness, or represent the interests of the United States in global commerce.

By contrast, big corporations headquartered in other rich nations are more responsible for the wellbeing of the people who live in those nations.

That’s because labor unions there are typically stronger than they are here — able to exert pressure both at the company level and nationally.

VW’s labor unions, for example, have a voice in governing the company, as they do in other big German corporations. Not long ago, VW even welcomed the UAW to its auto plant in Chattanooga, Tennessee. (Tennessee’s own politicians nixed it.)

Governments in other rich nations often devise laws through tri-partite bargains involving big corporations and organized labor. This process further binds their corporations to their nations.

Meanwhile, American corporations distribute a smaller share of their earnings to their workers than do European or Canadian-based corporations.

And top U.S. corporate executives make far more money than their counterparts in other wealthy countries.

The typical American worker puts in more hours than Canadians and Europeans, and gets little or no paid vacation or paid family leave. In Europe, the norm is five weeks paid vacation per year and more than three months paid family leave.

And because of the overwhelming clout of American firms on U.S. politics, Americans don’t get nearly as good a deal from their governments as do Canadians and Europeans.

Governments there impose higher taxes on the wealthy and redistribute more of it to middle and lower income households. Most of their citizens receive essentially free health care and more generous unemployment benefits than do Americans.

So it shouldn’t be surprising that even though U.S. economy is doing better, most Americans are not.

The U.S. middle class is no longer the world’s richest. After considering taxes and transfer payments, middle-class incomes in Canada and much of Western Europe are higher than in U.S. The poor in Western Europe earn more than do poor Americans.

Finally, when at global negotiating tables – such as the secretive process devising the “Trans Pacific Partnership” trade deal — American corporations don’t represent the interests of Americans. They represent the interests of their executives and shareholders, who are not only wealthier than most Americans but also reside all over the world.

Which is why the pending Partnership protects the intellectual property of American corporations — but not American workers’ health, safety, or wages, and not the environment.

The Obama administration is casting the Partnership as way to contain Chinese influence in the Pacific region. The agents of America’s interests in the area are assumed to be American corporations.

But that assumption is incorrect. American corporations aren’t set up to represent America’s interests in the Pacific region or anywhere else.

What’s the answer to this basic conundrum? Either we lessen the dominance of big American corporations over American politics. Or we increase their allegiance and responsibility to America.

It has to be one or the other. Americans can’t thrive within a political system run largely by big American corporations — organized to boost their share prices but not boost America.

Will the Democratic Nominee for 2016 Take on the Moneyed Interests?

Monday, March 2, 2015

It’s seed time for the 2016 presidential elections, when candidates try to figure out what they stand for and will run on.

One thing seems reasonably clear. The Democratic nominee for President, whoever she may be, will campaign on reviving the American middle class.

As will the Republican nominee — although the Republican nominee’s solution will almost certainly be warmed-over versions of George W. Bush’s “ownership society” and Mitt Romney’s “opportunity society,” both seeking to unleash the middle class’s entrepreneurial energies by reducing taxes and regulations.

That’s pretty much what we’ve heard from Republican hopefuls so far. As before, it will get us nowhere.

The Democratic nominee will just as surely call for easing the burdens on working parents through paid sick leave and paid family and medical leave, childcare, elder-care, a higher minimum wage, and perhaps also tax incentives for companies that share some of their profits with their employees.

All this is fine, but it won’t accomplish what’s really needed.

The big unknown is whether the Democratic nominee will also take on the moneyed interests – the large Wall Street banks, big corporations, and richest Americans – which have been responsible for the largest upward redistribution of income and wealth in modern American history.

Part of this upward redistribution has involved excessive risk-taking on Wall Street. Such excesses padded the nests of executives and traders but required a tax-payer funded bailout when the bubble burst in 2008. It also has caused millions of working Americans to lose their jobs, savings, and homes.

Since then, the Street has been back to many of its old tricks. Its lobbyists are also busily rolling back the Dodd-Frank Act intended to prevent another crash.

The Democratic candidate could condemn this, and go further — promising to resurrect the Glass-Steagall Act, once separating investment from commercial banking (until the Clinton administration joined with Republicans in repealing it in 1999).

The candidate could also call for busting up Wall Street’s biggest banks and thereafter limiting their size; imposing jail sentences on top executives who break the law; cracking down on insider trading; and, for good measure, enacting a small tax on all financial transactions in order to reduce speculation.

Another part of America’s upward redistribution has come in the form of “corporate welfare” – tax breaks and subsidies benefiting particular companies and industries (oil and gas, hedge-fund and private-equity, pharmaceuticals, big agriculture) for no other reason than they have the political clout to get them.

It’s also come in the guise of patents and trademarks that extend far beyond what’s necessary for adequate returns on corporate investment — resulting, for example, in drug prices that are higher in America than any other advanced nation.

It’s taken the form of monopoly power, generating outsize profits for certain companies (Monsanto, Pfizer, Comcast, for example) along with high prices for consumers.

And it’s come in the form of trade agreements that have greased the way for outsourcing American jobs abroad — thereby exerting downward pressure on American wages.

Not surprisingly, corporate profits now account for a largest percent of the total economy than they have in more than eight decades; and wages, the smallest percent in more than six.

The candidate could demand an end to corporate welfare and excessive intellectual property protection, along with tougher antitrust enforcement against giant firms with unwarranted market power.

And an end to trade agreements that take a big toll on wages of working-class Americans.

The candidate could also propose true tax reform: higher corporate taxes, in order to finance investments in education and infrastructure; ending all deductions of executive pay in excess of $1 million; and cracking down on corporations that shift profits to countries with lower taxes.

She (or he) could likewise demand higher taxes on America’s billionaires and multimillionaires – who have never been as wealthy, or taken home as high a percent of the nation’s total income and wealth — in order, for example, to finance an expanded Earned Income Tax Credit (a wage subsidy for low-income workers).

Not the least, taking on the moneyed interests would necessitate limiting their future political power. Here, the candidate could promise to appoint Supreme Court justices committed to reversing Citizens United, push for public financing of elections, and demand full disclosure of all private sources of campaign funding.

But will she (or he) do any of this? Taking on the moneyed interests is risky, especially when those interests have more economic and political power than at any time since the first Gilded Age. These interests are, after all, the main sources of campaign funding.

But a failure to take them on prevents any real change in the prospects of the bottom 90 percent of Americans.

It also robs the Democratic candidate of a potential public mandate to change the prevailing allocation of economic and political power — no less dramatically than it was changed by Teddy Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson a century ago, marking the end of that Gilded Age.

And a failure to take on the moneyed interests sacrifices the potential enthusiasm of millions of voters – Democrats and Republicans alike – who know the game is rigged, and who yearn for a leader with the strength and courage to un-rig it, and thereby give them and their children a fair chance.

One thing seems reasonably clear. The Democratic nominee for President, whoever she may be, will campaign on reviving the American middle class.

As will the Republican nominee — although the Republican nominee’s solution will almost certainly be warmed-over versions of George W. Bush’s “ownership society” and Mitt Romney’s “opportunity society,” both seeking to unleash the middle class’s entrepreneurial energies by reducing taxes and regulations.

That’s pretty much what we’ve heard from Republican hopefuls so far. As before, it will get us nowhere.

The Democratic nominee will just as surely call for easing the burdens on working parents through paid sick leave and paid family and medical leave, childcare, elder-care, a higher minimum wage, and perhaps also tax incentives for companies that share some of their profits with their employees.

All this is fine, but it won’t accomplish what’s really needed.

The big unknown is whether the Democratic nominee will also take on the moneyed interests – the large Wall Street banks, big corporations, and richest Americans – which have been responsible for the largest upward redistribution of income and wealth in modern American history.

Part of this upward redistribution has involved excessive risk-taking on Wall Street. Such excesses padded the nests of executives and traders but required a tax-payer funded bailout when the bubble burst in 2008. It also has caused millions of working Americans to lose their jobs, savings, and homes.

Since then, the Street has been back to many of its old tricks. Its lobbyists are also busily rolling back the Dodd-Frank Act intended to prevent another crash.

The Democratic candidate could condemn this, and go further — promising to resurrect the Glass-Steagall Act, once separating investment from commercial banking (until the Clinton administration joined with Republicans in repealing it in 1999).

The candidate could also call for busting up Wall Street’s biggest banks and thereafter limiting their size; imposing jail sentences on top executives who break the law; cracking down on insider trading; and, for good measure, enacting a small tax on all financial transactions in order to reduce speculation.

Another part of America’s upward redistribution has come in the form of “corporate welfare” – tax breaks and subsidies benefiting particular companies and industries (oil and gas, hedge-fund and private-equity, pharmaceuticals, big agriculture) for no other reason than they have the political clout to get them.

It’s also come in the guise of patents and trademarks that extend far beyond what’s necessary for adequate returns on corporate investment — resulting, for example, in drug prices that are higher in America than any other advanced nation.

It’s taken the form of monopoly power, generating outsize profits for certain companies (Monsanto, Pfizer, Comcast, for example) along with high prices for consumers.

And it’s come in the form of trade agreements that have greased the way for outsourcing American jobs abroad — thereby exerting downward pressure on American wages.

Not surprisingly, corporate profits now account for a largest percent of the total economy than they have in more than eight decades; and wages, the smallest percent in more than six.

The candidate could demand an end to corporate welfare and excessive intellectual property protection, along with tougher antitrust enforcement against giant firms with unwarranted market power.

And an end to trade agreements that take a big toll on wages of working-class Americans.

The candidate could also propose true tax reform: higher corporate taxes, in order to finance investments in education and infrastructure; ending all deductions of executive pay in excess of $1 million; and cracking down on corporations that shift profits to countries with lower taxes.

She (or he) could likewise demand higher taxes on America’s billionaires and multimillionaires – who have never been as wealthy, or taken home as high a percent of the nation’s total income and wealth — in order, for example, to finance an expanded Earned Income Tax Credit (a wage subsidy for low-income workers).

Not the least, taking on the moneyed interests would necessitate limiting their future political power. Here, the candidate could promise to appoint Supreme Court justices committed to reversing Citizens United, push for public financing of elections, and demand full disclosure of all private sources of campaign funding.

But will she (or he) do any of this? Taking on the moneyed interests is risky, especially when those interests have more economic and political power than at any time since the first Gilded Age. These interests are, after all, the main sources of campaign funding.

But a failure to take them on prevents any real change in the prospects of the bottom 90 percent of Americans.

It also robs the Democratic candidate of a potential public mandate to change the prevailing allocation of economic and political power — no less dramatically than it was changed by Teddy Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson a century ago, marking the end of that Gilded Age.

And a failure to take on the moneyed interests sacrifices the potential enthusiasm of millions of voters – Democrats and Republicans alike – who know the game is rigged, and who yearn for a leader with the strength and courage to un-rig it, and thereby give them and their children a fair chance.

Why We’re All Becoming Independent Contractors

Sunday, February 22, 2015

GM is worth around $60 billion, and has over 200,000 employees. Its front-line workers earn from $19 to $28.50 an hour, with benefits.

Uber is estimated to be worth some $40 billion, and has 850 employees. Uber also has over 163,000 drivers (as of December – the number is expected to double by June), who average $17 an hour in Los Angeles and Washington, D.C., and $23 an hour in San Francisco and New York.

But Uber doesn’t count these drivers as employees. Uber says they’re “independent contractors.”

What difference does it make?

For one thing, GM workers don’t have to pay for the machines they use. But Uber drivers pay for their cars – not just buying them but also their maintenance, insurance, gas, oil changes, tires, and cleaning. Subtract these costs and Uber drivers’ hourly pay drops considerably.

For another, GM’s employees get all the nation’s labor protections.

These include Social Security, a 40-hour workweek with time-and-a-half for overtime, worker health and safety, worker’s compensation if injured on the job, family and medical leave, minimum wage, pension protection, unemployment insurance, protection against racial or gender discrimination, and the right to bargain collectively.

Not to forget Obamacare’s mandate of employer-provided healthcare.

Uber workers don’t get any of these things. They’re outside the labor laws.

Uber workers aren’t alone. There are millions like just them, also outside the labor laws — and their ranks are growing. Most aren’t even part of the new Uberized “sharing” economy.

They’re franchisees, consultants, and free lancers.

They’re also construction workers, restaurant workers, truck drivers, office technicians, even workers in hair salons.

What they all have in common is they’re not considered “employees” of the companies they work for. They’re “independent contractors” – which puts all of them outside the labor laws, too.

The rise of “independent contractors” Is the most significant legal trend in the American workforce – contributing directly to low pay, irregular hours, and job insecurity.

What makes them “independent contractors” is the mainly that the companies they work for say they are. So those companies don’t have to pick up the costs of having full-time employees.

But are they really “independent”? Companies can manipulate their hours and expenses to make them seem so.

It’s become a race to the bottom. Once one business cuts costs by making its workers “independent contractors,” every other business in that industry has to do the same – or face shrinking profits and a dwindling share of the market

Some workers prefer to be independent contractors because that way they get paid in cash. Or they like deciding what hours they’ll work.

Mostly, though, they take these jobs because they can’t find better ones. And as the race to the bottom accelerates, they have fewer and fewer alternatives.

Fortunately, there are laws against this. Unfortunately, the laws are way too vague and not well-enforced.

For example, FedEx calls its drivers independent contractors.

Yet FedEx requires them to pay for the FedEx-branded trucks they drive, as well as the FedEx uniforms they wear, and FedEx scanners they use – along with insurance, fuel, tires, oil changes, meals on the road, maintenance, and workers compensation insurance. If they get sick or need a vacation, they have to hire their own replacements. They’re even required to groom themselves according to FedEx standards.

FedEx doesn’t tell its drivers what hours to work, but it tells them what packages to deliver and organizes their workloads to ensure they work between 9.5 and 11 hours every working day.

If this isn’t “employment,” I don’t know what the word means.

In 2005, thousands of FedEx drivers in California sued the company, alleging they were in fact employees and that FedEx owed them the money they shelled out, as well as wages for all the overtime work they put in.

Last summer, a federal appeals court agreed, finding that under California law – which looks at whether a company “controls” how a job is done along with a variety of other criteria to determine the real employment relationship – the FedEx drivers were indeed employees, not independent contractors.

Does that mean Uber drivers in California are also “employees”? That case is being considered right now.

What about FedEx drivers and Uber drivers in other states? Other truck drivers? Construction workers? Hair salon workers? The list goes on.

The law is still up in the air. Which means the race to the bottom is still on.

It’s absurd to wait for the courts to decide all this case-by-case. We need a simpler test for determining who’s an employer and employee.

I suggest this one: Any corporation that accounts for at least 80 percent or more of the pay someone gets, or receives from that worker at least 20 percent of his or her earnings, should be presumed to be that person’s “employer.”

Congress doesn’t have to pass a new law to make this the test of employment. Federal agencies such as the Labor Department and the IRS have the power to do this on their own, through their rule making authority.

They should do so. Now.

Uber is estimated to be worth some $40 billion, and has 850 employees. Uber also has over 163,000 drivers (as of December – the number is expected to double by June), who average $17 an hour in Los Angeles and Washington, D.C., and $23 an hour in San Francisco and New York.

But Uber doesn’t count these drivers as employees. Uber says they’re “independent contractors.”

What difference does it make?

For one thing, GM workers don’t have to pay for the machines they use. But Uber drivers pay for their cars – not just buying them but also their maintenance, insurance, gas, oil changes, tires, and cleaning. Subtract these costs and Uber drivers’ hourly pay drops considerably.

For another, GM’s employees get all the nation’s labor protections.

These include Social Security, a 40-hour workweek with time-and-a-half for overtime, worker health and safety, worker’s compensation if injured on the job, family and medical leave, minimum wage, pension protection, unemployment insurance, protection against racial or gender discrimination, and the right to bargain collectively.

Not to forget Obamacare’s mandate of employer-provided healthcare.

Uber workers don’t get any of these things. They’re outside the labor laws.

Uber workers aren’t alone. There are millions like just them, also outside the labor laws — and their ranks are growing. Most aren’t even part of the new Uberized “sharing” economy.

They’re franchisees, consultants, and free lancers.

They’re also construction workers, restaurant workers, truck drivers, office technicians, even workers in hair salons.

What they all have in common is they’re not considered “employees” of the companies they work for. They’re “independent contractors” – which puts all of them outside the labor laws, too.

The rise of “independent contractors” Is the most significant legal trend in the American workforce – contributing directly to low pay, irregular hours, and job insecurity.

What makes them “independent contractors” is the mainly that the companies they work for say they are. So those companies don’t have to pick up the costs of having full-time employees.

But are they really “independent”? Companies can manipulate their hours and expenses to make them seem so.

It’s become a race to the bottom. Once one business cuts costs by making its workers “independent contractors,” every other business in that industry has to do the same – or face shrinking profits and a dwindling share of the market

Some workers prefer to be independent contractors because that way they get paid in cash. Or they like deciding what hours they’ll work.

Mostly, though, they take these jobs because they can’t find better ones. And as the race to the bottom accelerates, they have fewer and fewer alternatives.

Fortunately, there are laws against this. Unfortunately, the laws are way too vague and not well-enforced.

For example, FedEx calls its drivers independent contractors.

Yet FedEx requires them to pay for the FedEx-branded trucks they drive, as well as the FedEx uniforms they wear, and FedEx scanners they use – along with insurance, fuel, tires, oil changes, meals on the road, maintenance, and workers compensation insurance. If they get sick or need a vacation, they have to hire their own replacements. They’re even required to groom themselves according to FedEx standards.

FedEx doesn’t tell its drivers what hours to work, but it tells them what packages to deliver and organizes their workloads to ensure they work between 9.5 and 11 hours every working day.

If this isn’t “employment,” I don’t know what the word means.

In 2005, thousands of FedEx drivers in California sued the company, alleging they were in fact employees and that FedEx owed them the money they shelled out, as well as wages for all the overtime work they put in.

Last summer, a federal appeals court agreed, finding that under California law – which looks at whether a company “controls” how a job is done along with a variety of other criteria to determine the real employment relationship – the FedEx drivers were indeed employees, not independent contractors.

Does that mean Uber drivers in California are also “employees”? That case is being considered right now.

What about FedEx drivers and Uber drivers in other states? Other truck drivers? Construction workers? Hair salon workers? The list goes on.

The law is still up in the air. Which means the race to the bottom is still on.

It’s absurd to wait for the courts to decide all this case-by-case. We need a simpler test for determining who’s an employer and employee.

I suggest this one: Any corporation that accounts for at least 80 percent or more of the pay someone gets, or receives from that worker at least 20 percent of his or her earnings, should be presumed to be that person’s “employer.”

Congress doesn’t have to pass a new law to make this the test of employment. Federal agencies such as the Labor Department and the IRS have the power to do this on their own, through their rule making authority.

They should do so. Now.

The President Should Not Only Veto the Keystone XL Pipeline but Stop it Permanently

The President says he’ll veto the Keystone XL pipeline. He should do more, and put an end to the project altogether. He has the authority. Oil from Alberta’s tar sands is the dirtiest in the world – causing not just serious environmental damage when it’s extracted but also when and if it leaks out along its route from Canada to the Gulf of Mexico. Please tell the White House to veto it permanently.

The President says he’ll veto the Keystone XL pipeline. He should do more, and put an end to the project altogether. He has the authority. Oil from Alberta’s tar sands is the dirtiest in the world – causing not just serious environmental damage when it’s extracted but also when and if it leaks out along its route from Canada to the Gulf of Mexico. Please tell the White House to veto it permanently.

How Trade Deals Boost the Top 1% and Bust the Rest

Monday, February 16, 2015

Suppose that by enacting a particular law we’d

increase the U.S.Gross Domestic Product. But almost all that growth

would go to the richest 1percent.

The rest of us could buy some products cheaper than before. But those gains would be offset by losses of jobs and wages.

This is pretty much what “free trade” has brought us over the last two decades.

I used to believe in trade agreements. That was before the wages of most Americans stagnated and a relative few at the top captured just about all the economic gains.

Recent trade agreements have been wins for big corporations and Wall Street, along with their executives and major shareholders. They get better access to foreign markets and billions of consumers.

They also get better protection for their intellectual property – patents, trademarks, and copyrights. And for their overseas factories, equipment, and financial assets.

But those deals haven’t been wins for most Americans.

The fact is, trade agreements are no longer really about trade. Worldwide tariffs are already low. Big American corporations no longer make many products in the United States for export abroad.

The biggest things big American corporations sell overseas are ideas, designs, franchises, brands, engineering solutions, instructions, and software.

Google, Apple, Uber, Facebook, Walmart, McDonalds, Microsoft, and Pfizer, for example, are making huge profits all over the world.

But those profits don’t depend on American labor — apart from a tiny group of managers, designers, and researchers in the U.S.

To the extent big American-based corporations any longer make stuff for export, they make most of it abroad and then export it from there, for sale all over the world — including for sale back here in the United States.

The Apple iPhone is assembled in China from components made in Japan, Singapore, and a half-dozen other locales. The only things coming from the U.S. are designs and instructions from a handful of engineers and managers in California.

Apple even stows most of its profits outside the U.S. so it doesn’t have to pay American taxes on them.

This is why big American companies are less interested than they once were in opening other countries to goods exported from the United States and made by American workers.

They’re more interested in making sure other countries don’t run off with their patented designs and trademarks. Or restrict where they can put and shift their profits.

In fact, today’s “trade agreements” should really be called “global corporate agreements” because they’re mostly about protecting the assets and profits of these global corporations rather than increasing American jobs and wages. The deals don’t even guard against currency manipulation by other nations.

According to Economic Policy Institute, the North American Free Trade Act cost U.S. workers almost 700,000 jobs, thereby pushing down American wages.

Since the passage of the Korea–U.S. Free Trade Agreement, America’s trade deficit with Korea has grown more than 80 percent, equivalent to a loss of more than 70,000 additional U.S. jobs.

The U.S. goods trade deficit with China increased $23.9 billion last year, to $342.6 billion. Again, the ultimate result has been to keep U.S. wages down.

The old-style trade agreements of the 1960s and 1970s increased worldwide demand for products made by American workers, and thereby helped push up American wages.

The new-style global corporate agreements mainly enhance corporate and financial profits, and push down wages.

That’s why big corporations and Wall Street are so enthusiastic about the upcoming Trans Pacific Partnership – the giant deal among countries responsible for 40 percent of the global economy.

That deal would give giant corporations even more patent protection overseas. It would also guard their overseas profits.

And it would allow them to challenge any nation’s health, safety, and environmental laws that stand in the way of their profits – including our own.

The Administration calls the Trans Pacific Partnership a key part of its “strategy to make U.S. engagement in the Asia-Pacific region a top priority.”

Translated: The White House thinks it will help the U.S. contain China’s power and influence.

But it will make giant U.S. global corporations even more powerful and influential.

White House strategists seem to think such corporations are accountable to the U.S. government. Wrong. At most, they’re answerable to their shareholders, who demand high share prices whatever that requires.

I’ve seen first-hand how effective Wall Street and big corporations are at wielding influence — using lobbyists, campaign donations, and subtle promises of future jobs to get the global deals they want.

Global deals like the Trans Pacific Partnership will boost the profits of Wall Street and big corporations, and make the richest 1 percent even richer.

But they’ll bust the rest of America.

The rest of us could buy some products cheaper than before. But those gains would be offset by losses of jobs and wages.

This is pretty much what “free trade” has brought us over the last two decades.

I used to believe in trade agreements. That was before the wages of most Americans stagnated and a relative few at the top captured just about all the economic gains.

Recent trade agreements have been wins for big corporations and Wall Street, along with their executives and major shareholders. They get better access to foreign markets and billions of consumers.

They also get better protection for their intellectual property – patents, trademarks, and copyrights. And for their overseas factories, equipment, and financial assets.

But those deals haven’t been wins for most Americans.

The fact is, trade agreements are no longer really about trade. Worldwide tariffs are already low. Big American corporations no longer make many products in the United States for export abroad.

The biggest things big American corporations sell overseas are ideas, designs, franchises, brands, engineering solutions, instructions, and software.

Google, Apple, Uber, Facebook, Walmart, McDonalds, Microsoft, and Pfizer, for example, are making huge profits all over the world.

But those profits don’t depend on American labor — apart from a tiny group of managers, designers, and researchers in the U.S.

To the extent big American-based corporations any longer make stuff for export, they make most of it abroad and then export it from there, for sale all over the world — including for sale back here in the United States.

The Apple iPhone is assembled in China from components made in Japan, Singapore, and a half-dozen other locales. The only things coming from the U.S. are designs and instructions from a handful of engineers and managers in California.

Apple even stows most of its profits outside the U.S. so it doesn’t have to pay American taxes on them.

This is why big American companies are less interested than they once were in opening other countries to goods exported from the United States and made by American workers.

They’re more interested in making sure other countries don’t run off with their patented designs and trademarks. Or restrict where they can put and shift their profits.

In fact, today’s “trade agreements” should really be called “global corporate agreements” because they’re mostly about protecting the assets and profits of these global corporations rather than increasing American jobs and wages. The deals don’t even guard against currency manipulation by other nations.

According to Economic Policy Institute, the North American Free Trade Act cost U.S. workers almost 700,000 jobs, thereby pushing down American wages.

Since the passage of the Korea–U.S. Free Trade Agreement, America’s trade deficit with Korea has grown more than 80 percent, equivalent to a loss of more than 70,000 additional U.S. jobs.

The U.S. goods trade deficit with China increased $23.9 billion last year, to $342.6 billion. Again, the ultimate result has been to keep U.S. wages down.

The old-style trade agreements of the 1960s and 1970s increased worldwide demand for products made by American workers, and thereby helped push up American wages.

The new-style global corporate agreements mainly enhance corporate and financial profits, and push down wages.

That’s why big corporations and Wall Street are so enthusiastic about the upcoming Trans Pacific Partnership – the giant deal among countries responsible for 40 percent of the global economy.

That deal would give giant corporations even more patent protection overseas. It would also guard their overseas profits.

And it would allow them to challenge any nation’s health, safety, and environmental laws that stand in the way of their profits – including our own.

The Administration calls the Trans Pacific Partnership a key part of its “strategy to make U.S. engagement in the Asia-Pacific region a top priority.”

Translated: The White House thinks it will help the U.S. contain China’s power and influence.

But it will make giant U.S. global corporations even more powerful and influential.

White House strategists seem to think such corporations are accountable to the U.S. government. Wrong. At most, they’re answerable to their shareholders, who demand high share prices whatever that requires.

I’ve seen first-hand how effective Wall Street and big corporations are at wielding influence — using lobbyists, campaign donations, and subtle promises of future jobs to get the global deals they want.

Global deals like the Trans Pacific Partnership will boost the profits of Wall Street and big corporations, and make the richest 1 percent even richer.

But they’ll bust the rest of America.

Back to the Nineteenth Century

Monday, February 9, 2015

My recent column about the growth of on-demand

jobs like Uber making life less predictable and secure for workers

unleashed a small barrage of criticism from some who contend that

workers get what they’re worth in the market.

A Forbes Magazine contributor, for example, writes that jobs exist only “when both employer and employee are happy with the deal being made.” So if the new jobs are low-paying and irregular, too bad.

Much the same argument was voiced in the late nineteenth century over alleged “freedom of contract.” Any deal between employees and workers was assumed to be fine if both sides voluntarily agreed to it.

It was an era when many workers were “happy” to toil twelve-hour days in sweat shops for lack of any better alternative.

It was also a time of great wealth for a few and squalor for many. And of corruption, as the lackeys of robber barons deposited sacks of cash on the desks of pliant legislators.

Finally, after decades of labor strife and political tumult, the twentieth century brought an understanding that capitalism requires minimum standards of decency and fairness – workplace safety, a minimum wage, maximum hours (and time-and-a-half for overtime), and a ban on child labor.

We also learned that capitalism needs a fair balance of power between big corporations and workers.

We achieved that through antitrust laws that reduced the capacity of giant corporations to impose their will, and labor laws that allowed workers to organize and bargain collectively.

By the 1950s, when 35 percent of private-sector workers belonged to a labor union, they were able to negotiate higher wages and better working conditions than employers would otherwise have been “happy” to provide.

But now we seem to be heading back to nineteenth century.

Corporations are shifting full-time work onto temps, free-lancers, and contract workers who fall outside the labor protections established decades ago.

The nation’s biggest corporations and Wall Street banks are larger and more potent than ever.

And labor union membership has shrunk to fewer than 7 percent of private-sector workers.

So it’s not surprising we’re once again hearing that workers are worth no more than what they can get in the market.

But as we should have learned a century ago, markets don’t exist in nature. They’re created by human beings. The real question is how they’re organized and for whose benefit.

In the late nineteenth century they were organized for the benefit of a few at the top.

But by the middle of the twentieth century they were organized for the vast majority.

During the thirty years after the end of World War II, as the economy doubled in size, so did the wages of most Americans — along with improved hours and working conditions.

Yet since around 1980, even though the economy has doubled once again (the Great Recession notwithstanding), the wages most Americans have stagnated. And their benefits and working conditions have deteriorated.

This isn’t because most Americans are worth less. In fact, worker productivity is higher than ever.

It’s because big corporations, Wall Street, and some enormously rich individuals have gained political power to organize the market in ways that have enhanced their wealth while leaving most Americans behind.

That includes trade agreements protecting the intellectual property of large corporations and Wall Street’s financial assets, but not American jobs and wages.

Bailouts of big Wall Street banks and their executives and shareholders when they can’t pay what they owe, but not of homeowners who can’t meet their mortgage payments.

Bankruptcy protection for big corporations, allowing them to shed their debts, including labor contracts. But no bankruptcy protection for college graduates over-burdened with student debts.

Antitrust leniency toward a vast swathe of American industry – including Big Cable (Comcast, AT&T, Time-Warner), Big Tech (Amazon, Google), Big Pharma, the largest Wall Street banks, and giant retailers (Walmart).

But less tolerance toward labor unions — as workers trying to form unions are fired with impunity, and more states adopt so-called “right-to-work” laws that undermine unions.

We seem to be heading full speed back to the late nineteenth century.

So what will be the galvanizing force for change this time?

A Forbes Magazine contributor, for example, writes that jobs exist only “when both employer and employee are happy with the deal being made.” So if the new jobs are low-paying and irregular, too bad.

Much the same argument was voiced in the late nineteenth century over alleged “freedom of contract.” Any deal between employees and workers was assumed to be fine if both sides voluntarily agreed to it.

It was an era when many workers were “happy” to toil twelve-hour days in sweat shops for lack of any better alternative.

It was also a time of great wealth for a few and squalor for many. And of corruption, as the lackeys of robber barons deposited sacks of cash on the desks of pliant legislators.

Finally, after decades of labor strife and political tumult, the twentieth century brought an understanding that capitalism requires minimum standards of decency and fairness – workplace safety, a minimum wage, maximum hours (and time-and-a-half for overtime), and a ban on child labor.

We also learned that capitalism needs a fair balance of power between big corporations and workers.

We achieved that through antitrust laws that reduced the capacity of giant corporations to impose their will, and labor laws that allowed workers to organize and bargain collectively.

By the 1950s, when 35 percent of private-sector workers belonged to a labor union, they were able to negotiate higher wages and better working conditions than employers would otherwise have been “happy” to provide.

But now we seem to be heading back to nineteenth century.

Corporations are shifting full-time work onto temps, free-lancers, and contract workers who fall outside the labor protections established decades ago.

The nation’s biggest corporations and Wall Street banks are larger and more potent than ever.

And labor union membership has shrunk to fewer than 7 percent of private-sector workers.

So it’s not surprising we’re once again hearing that workers are worth no more than what they can get in the market.

But as we should have learned a century ago, markets don’t exist in nature. They’re created by human beings. The real question is how they’re organized and for whose benefit.

In the late nineteenth century they were organized for the benefit of a few at the top.

But by the middle of the twentieth century they were organized for the vast majority.

During the thirty years after the end of World War II, as the economy doubled in size, so did the wages of most Americans — along with improved hours and working conditions.

Yet since around 1980, even though the economy has doubled once again (the Great Recession notwithstanding), the wages most Americans have stagnated. And their benefits and working conditions have deteriorated.

This isn’t because most Americans are worth less. In fact, worker productivity is higher than ever.

It’s because big corporations, Wall Street, and some enormously rich individuals have gained political power to organize the market in ways that have enhanced their wealth while leaving most Americans behind.

That includes trade agreements protecting the intellectual property of large corporations and Wall Street’s financial assets, but not American jobs and wages.

Bailouts of big Wall Street banks and their executives and shareholders when they can’t pay what they owe, but not of homeowners who can’t meet their mortgage payments.

Bankruptcy protection for big corporations, allowing them to shed their debts, including labor contracts. But no bankruptcy protection for college graduates over-burdened with student debts.

Antitrust leniency toward a vast swathe of American industry – including Big Cable (Comcast, AT&T, Time-Warner), Big Tech (Amazon, Google), Big Pharma, the largest Wall Street banks, and giant retailers (Walmart).

But less tolerance toward labor unions — as workers trying to form unions are fired with impunity, and more states adopt so-called “right-to-work” laws that undermine unions.

We seem to be heading full speed back to the late nineteenth century.

So what will be the galvanizing force for change this time?

The Share-the-Scraps Economy

Monday, February 2, 2015

How would you like to live in an economy where

robots do everything that can be predictably programmed in advance, and

almost all profits go to the robots’ owners?

Meanwhile, human beings do the work that’s unpredictable – odd jobs, on-call projects, fetching and fixing, driving and delivering, tiny tasks needed at any and all hours – and patch together barely enough to live on.

Brace yourself. This is the economy we’re now barreling toward.

They’re Uber drivers, Instacart shoppers, and Airbnb hosts. They include Taskrabbit jobbers, Upcounsel’s on-demand attorneys, and Healthtap’s on-line doctors.

They’re Mechanical Turks.

The euphemism is the “share” economy. A more accurate term would be the “share-the-scraps” economy.

New software technologies are allowing almost any job to be divided up into discrete tasks that can be parceled out to workers when they’re needed, with pay determined by demand for that particular job at that particular moment.

Customers and workers are matched online. Workers are rated on quality and reliability.

The big money goes to the corporations that own the software. The scraps go to the on-demand workers.

Consider Amazon’s “Mechanical Turk.” Amazon calls it “a marketplace for work that requires human intelligence.”

In reality, it’s an Internet job board offering minimal pay for mindlessly-boring bite-sized chores. Computers can’t do them because they require some minimal judgment, so human beings do them for peanuts — say, writing a product description, for $3; or choosing the best of several photographs, for 30 cents; or deciphering handwriting, for 50 cents.

Amazon takes a healthy cut of every transaction.

This is the logical culmination of a process that began thirty years ago when corporations began turning over full-time jobs to temporary workers, independent contractors, free-lancers, and consultants.

It was a way to shift risks and uncertainties onto the workers – work that might entail more hours than planned for, or was more stressful than expected.

And a way to circumvent labor laws that set minimal standards for wages, hours, and working conditions. And that enabled employees to join together to bargain for better pay and benefits.

The new on-demand work shifts risks entirely onto workers, and eliminates minimal standards completely.

In effect, on-demand work is a reversion to the piece work of the nineteenth century – when workers had no power and no legal rights, took all the risks, and worked all hours for almost nothing.

Uber drivers use their own cars, take out their own insurance, work as many hours as they want or can – and pay Uber a fat percent. Worker safety? Social Security? Uber says it’s not the employer so it’s not responsible.

Amazon’s Mechanical Turks work for pennies, literally. Minimum wage? Time-and-a half for overtime? Amazon says it just connects buyers and sellers so it’s not responsible.

Defenders of on-demand work emphasize its flexibility. Workers can put in whatever time they want, work around their schedules, fill in the downtime in their calendars.

“People are monetizing their own downtime,” Arun Sundararajan, a professor at New York University’s business school, told the New York Times.

But this argument confuses “downtime” with the time people normally reserve for the rest of their lives.

There are still only twenty-four hours in a day. When “downtime” is turned into work time, and that work time is unpredictable and low-paid, what happens to personal relationships? Family? One’s own health?

Other proponents of on-demand work point to studies, such as one recently commissioned by Uber, showing Uber’s on-demand workers to be “happy.”

But how many of them would be happier with a good-paying job offering regular hours?

An opportunity to make some extra bucks can seem mighty attractive in an economy whose median wage has been stagnant for thirty years and almost all of whose economic gains have been going to the top.

That doesn’t make the opportunity a great deal. It only shows how bad a deal most working people have otherwise been getting.

Defenders also point out that as on-demand work continues to grow, on-demand workers are joining together in guild-like groups to buy insurance and other benefits.

But, notably, they aren’t using their bargaining power to get a larger share of the income they pull in, or steadier hours. That would be a union – something that Uber, Amazon, and other on-demand companies don’t want.

Some economists laud on-demand work as a means of utilizing people more efficiently.

But the biggest economic challenge we face isn’t using people more efficiently. It’s allocating work and the gains from work more decently.

On this measure, the share-the-scraps economy is hurtling us backwards.

Meanwhile, human beings do the work that’s unpredictable – odd jobs, on-call projects, fetching and fixing, driving and delivering, tiny tasks needed at any and all hours – and patch together barely enough to live on.

Brace yourself. This is the economy we’re now barreling toward.

They’re Uber drivers, Instacart shoppers, and Airbnb hosts. They include Taskrabbit jobbers, Upcounsel’s on-demand attorneys, and Healthtap’s on-line doctors.

They’re Mechanical Turks.

The euphemism is the “share” economy. A more accurate term would be the “share-the-scraps” economy.

New software technologies are allowing almost any job to be divided up into discrete tasks that can be parceled out to workers when they’re needed, with pay determined by demand for that particular job at that particular moment.

Customers and workers are matched online. Workers are rated on quality and reliability.

The big money goes to the corporations that own the software. The scraps go to the on-demand workers.

Consider Amazon’s “Mechanical Turk.” Amazon calls it “a marketplace for work that requires human intelligence.”

In reality, it’s an Internet job board offering minimal pay for mindlessly-boring bite-sized chores. Computers can’t do them because they require some minimal judgment, so human beings do them for peanuts — say, writing a product description, for $3; or choosing the best of several photographs, for 30 cents; or deciphering handwriting, for 50 cents.

Amazon takes a healthy cut of every transaction.

This is the logical culmination of a process that began thirty years ago when corporations began turning over full-time jobs to temporary workers, independent contractors, free-lancers, and consultants.

It was a way to shift risks and uncertainties onto the workers – work that might entail more hours than planned for, or was more stressful than expected.

And a way to circumvent labor laws that set minimal standards for wages, hours, and working conditions. And that enabled employees to join together to bargain for better pay and benefits.

The new on-demand work shifts risks entirely onto workers, and eliminates minimal standards completely.

In effect, on-demand work is a reversion to the piece work of the nineteenth century – when workers had no power and no legal rights, took all the risks, and worked all hours for almost nothing.

Uber drivers use their own cars, take out their own insurance, work as many hours as they want or can – and pay Uber a fat percent. Worker safety? Social Security? Uber says it’s not the employer so it’s not responsible.

Amazon’s Mechanical Turks work for pennies, literally. Minimum wage? Time-and-a half for overtime? Amazon says it just connects buyers and sellers so it’s not responsible.

Defenders of on-demand work emphasize its flexibility. Workers can put in whatever time they want, work around their schedules, fill in the downtime in their calendars.

“People are monetizing their own downtime,” Arun Sundararajan, a professor at New York University’s business school, told the New York Times.

But this argument confuses “downtime” with the time people normally reserve for the rest of their lives.

There are still only twenty-four hours in a day. When “downtime” is turned into work time, and that work time is unpredictable and low-paid, what happens to personal relationships? Family? One’s own health?

Other proponents of on-demand work point to studies, such as one recently commissioned by Uber, showing Uber’s on-demand workers to be “happy.”

But how many of them would be happier with a good-paying job offering regular hours?

An opportunity to make some extra bucks can seem mighty attractive in an economy whose median wage has been stagnant for thirty years and almost all of whose economic gains have been going to the top.

That doesn’t make the opportunity a great deal. It only shows how bad a deal most working people have otherwise been getting.

Defenders also point out that as on-demand work continues to grow, on-demand workers are joining together in guild-like groups to buy insurance and other benefits.

But, notably, they aren’t using their bargaining power to get a larger share of the income they pull in, or steadier hours. That would be a union – something that Uber, Amazon, and other on-demand companies don’t want.

Some economists laud on-demand work as a means of utilizing people more efficiently.

But the biggest economic challenge we face isn’t using people more efficiently. It’s allocating work and the gains from work more decently.

On this measure, the share-the-scraps economy is hurtling us backwards.

The Worst Trade Deal You Never Heard Of

The Trans-Pacific Partnership, now headed to Congress, is a product of big corporations and Wall Street, seeking to circumvent regulations protecting workers, consumers, and the environment. Watch this video, and say “no” to fast-tracking this bad deal for the vast majority of Americans.

The Trans-Pacific Partnership, now headed to Congress, is a product of big corporations and Wall Street, seeking to circumvent regulations protecting workers, consumers, and the environment. Watch this video, and say “no” to fast-tracking this bad deal for the vast majority of Americans.

The 3 Biggest Myths Blinding Us to the Economic Truth

1. The “job creators” are CEOs, corporations, and the rich, whose taxes must be low in order to induce them to create more jobs. Rubbish. The real job creators are the vast middle class and the poor, whose spending induces businesses to create jobs. Which is why raising the minimum wage, extending overtime protection, enlarging the Earned Income Tax Credit, and reducing middle-class taxes are all necessary.

2. The critical choice is between the “free market” or “government.” Baloney. The free market doesn’t exist in nature. It’s created and enforced by government. And all the ongoing decisions about how it’s organized – what gets patent protection and for how long (the human genome?), who can declare bankruptcy (corporations? homeowners? student debtors?), what contracts are fraudulent (insider trading?) or coercive (predatory loans? mandatory arbitration?), and how much market power is excessive (Comcast and Time Warner?) – depend on government.

3. We should worry most about the size of government. Wrong. We should worry about who government is for. When big money from giant corporations and Wall Street inundate our politics, all decisions relating to #1 and #2 above become rigged against average working Americans.

Please take a look at our video, and share.

1. The “job creators” are CEOs, corporations, and the rich, whose taxes must be low in order to induce them to create more jobs. Rubbish. The real job creators are the vast middle class and the poor, whose spending induces businesses to create jobs. Which is why raising the minimum wage, extending overtime protection, enlarging the Earned Income Tax Credit, and reducing middle-class taxes are all necessary.

2. The critical choice is between the “free market” or “government.” Baloney. The free market doesn’t exist in nature. It’s created and enforced by government. And all the ongoing decisions about how it’s organized – what gets patent protection and for how long (the human genome?), who can declare bankruptcy (corporations? homeowners? student debtors?), what contracts are fraudulent (insider trading?) or coercive (predatory loans? mandatory arbitration?), and how much market power is excessive (Comcast and Time Warner?) – depend on government.

3. We should worry most about the size of government. Wrong. We should worry about who government is for. When big money from giant corporations and Wall Street inundate our politics, all decisions relating to #1 and #2 above become rigged against average working Americans.

Please take a look at our video, and share.

The President Should Not Only Veto the Keystone XL Pipeline but Stop it Permanently

The President says he’ll veto the Keystone XL pipeline. He should do more, and put an end to the project altogether. He has the authority. Oil from Alberta’s tar sands is the dirtiest in the world – causing not just serious environmental damage when it’s extracted but also when and if it leaks out along its route from Canada to the Gulf of Mexico. Please tell the White House to veto it permanently.

The President says he’ll veto the Keystone XL pipeline. He should do more, and put an end to the project altogether. He has the authority. Oil from Alberta’s tar sands is the dirtiest in the world – causing not just serious environmental damage when it’s extracted but also when and if it leaks out along its route from Canada to the Gulf of Mexico. Please tell the White House to veto it permanently.

The Worst Trade Deal You Never Heard Of

The Trans-Pacific Partnership, now headed to Congress, is a product of big corporations and Wall Street, seeking to circumvent regulations protecting workers, consumers, and the environment. Watch this video, and say “no” to fast-tracking this bad deal for the vast majority of Americans.

The Trans-Pacific Partnership, now headed to Congress, is a product of big corporations and Wall Street, seeking to circumvent regulations protecting workers, consumers, and the environment. Watch this video, and say “no” to fast-tracking this bad deal for the vast majority of Americans.

Out with 2014, In with 2015, and Up with People

We’ve made progress this year — raising the minimum wage in dozens of states and cities, providing equal marriage rights in a majority of states, limiting carbon emissions. But there’s far more to do.